May the injustices and humiliation suffered here as a result of hysteria, racism, and economic exploitation never emerge again.

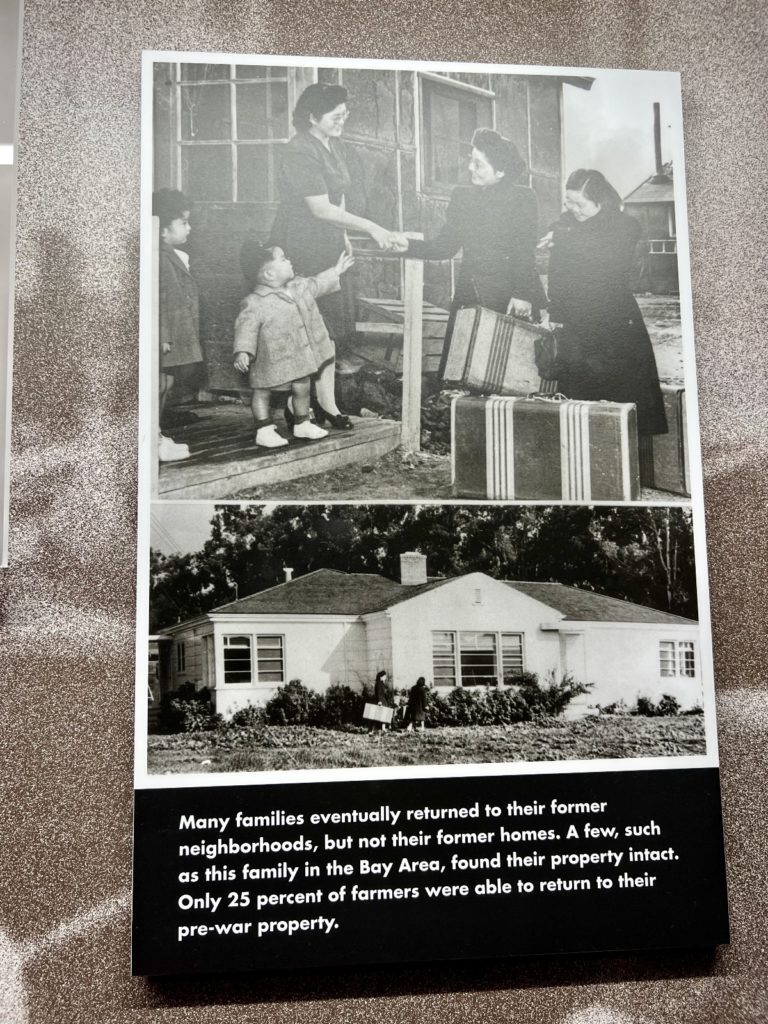

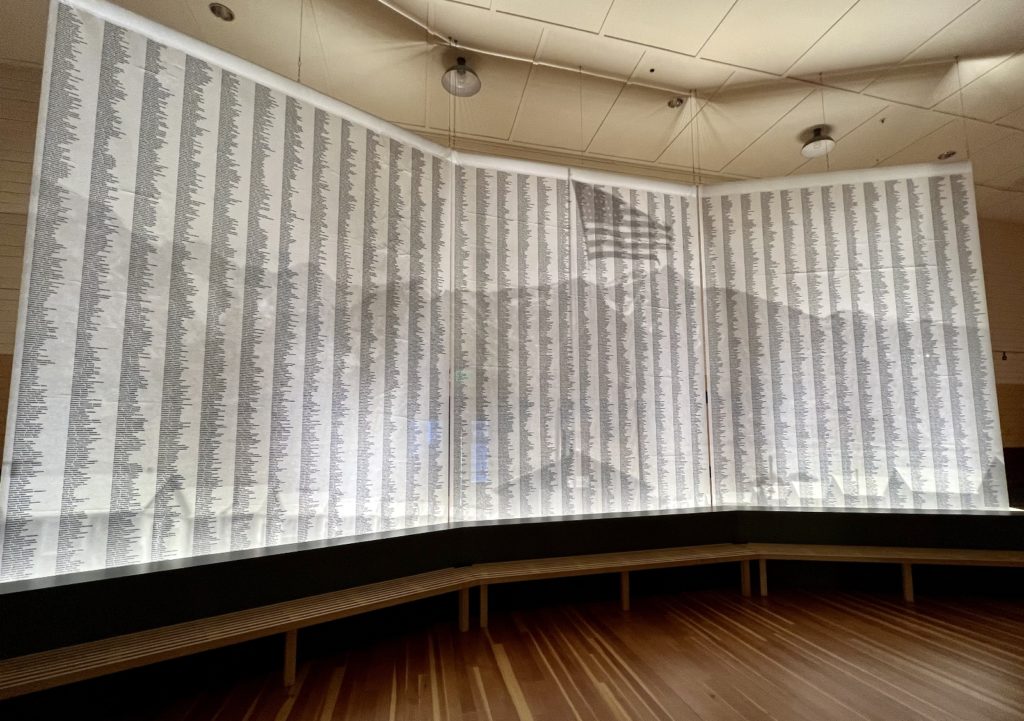

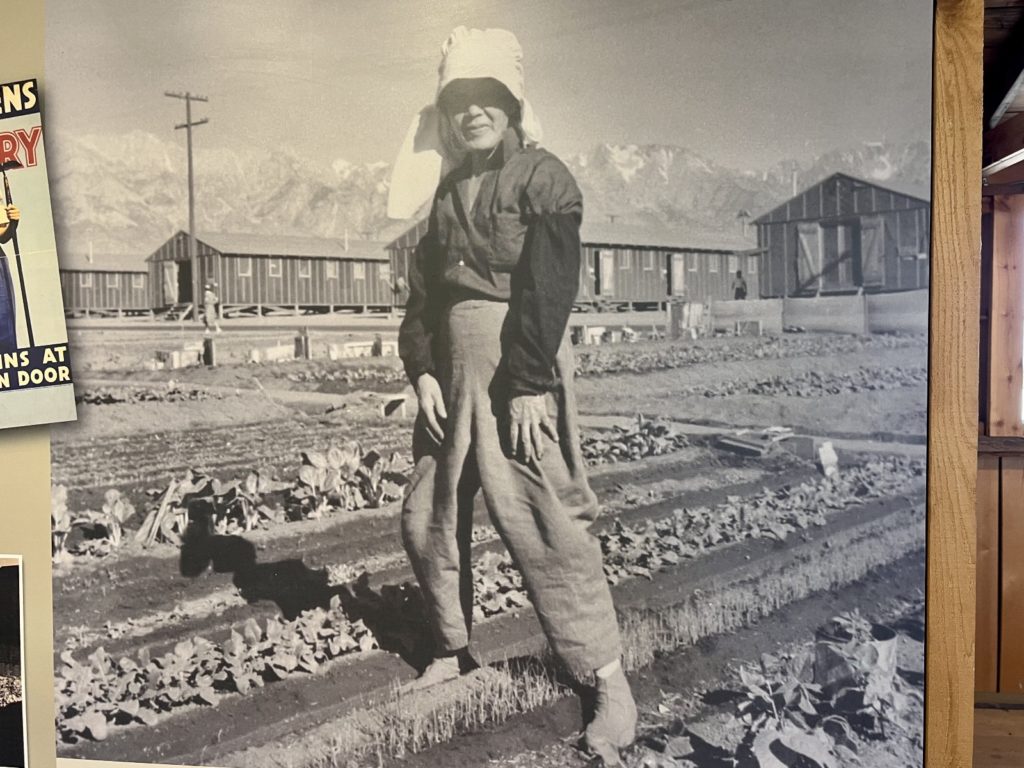

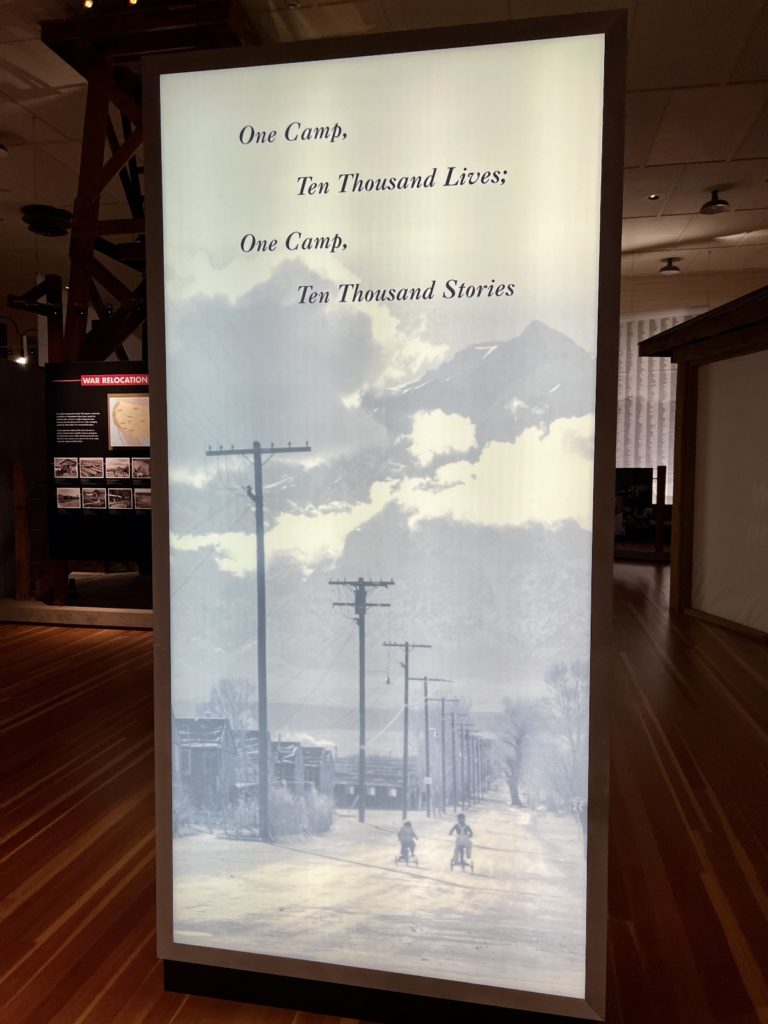

From 1942 to 1945, the United States government ordered more than 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry to be interned in relocation centers under Executive Order No 9066. Accused of no crime except their ancestry, they were forced to leave their homes and were detained in remote, military style camps. Two-thirds of them were born in America. Not one was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage. For more than 10,000 of them, Manzanar War Relocation Center would be their new home.

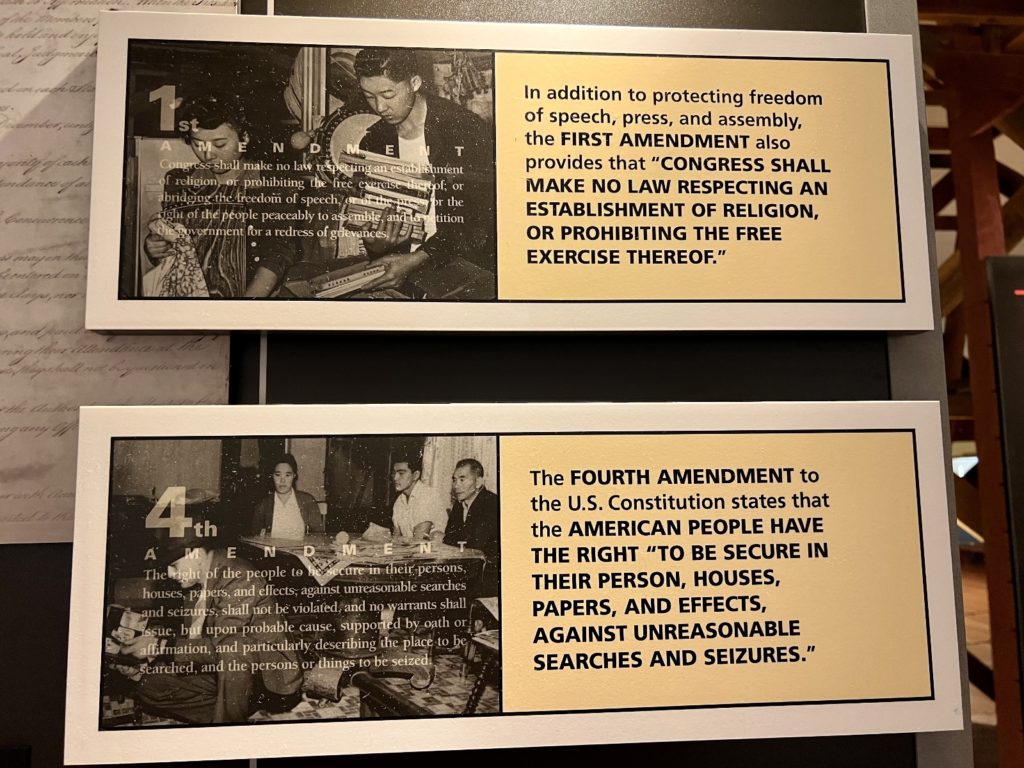

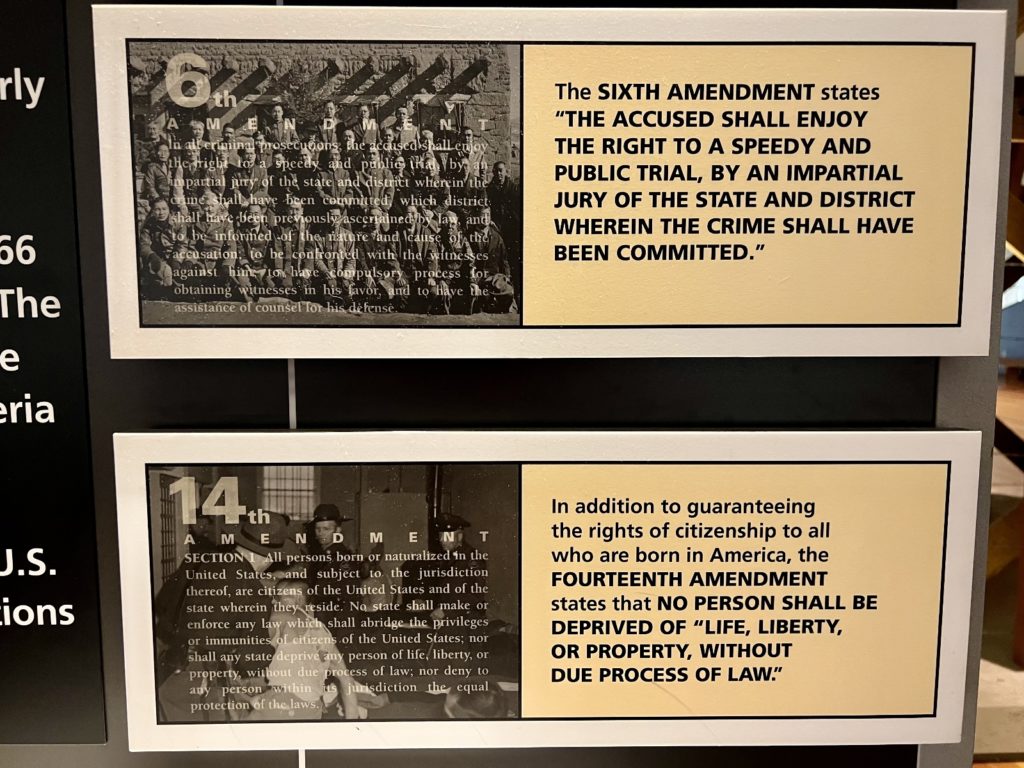

Today, Manzanar National Historic Site, a unit of the National Park Service, preserves the first of ten war relocation centers created under Executive Order No 9066 and honors the memory of those who were confined there. A visit to Manzanar is an immersion into one of our nation’s darkest chapters and is a sobering experience. As Americans, believe we enjoy certain rights and freedoms. We believe such atrocities could never happen to us or our family. Manzanar challenges these notions. What guarantees your constitutional rights when they were so easily trampled for other citizens? Is our cultural and political landscape really so improved today? I encourage you to make a visit to Manzanar. For those with an open mind, I believe the images and stories of those who called Manzanar home will cause you deep reflection.

My motivation for visiting Manzanar was two-fold. First, I’m a United States history buff who jumps at every opportunity to visit new sites. I’ve always been interested in what happened at a given location. As time passes and the world around us seems to become a little crazier with each passing day, I’m increasingly interested in why events happened. Manzanar is a great place to reflect on why. Second, one of my dearest friends had family who were interned under Order 9066. They were honest, hard-working, proud Americans who happened to be of Japanese ancestry. My mind couldn’t reconcile innocent people losing their homes, jobs, and land, literally overnight. Many of my ancestors were German, yet very few Germans were interned despite the actions of the Nazis. Why was my friend’s family imprisoned and not my own?

Japanese Immigrants Prior to WWII

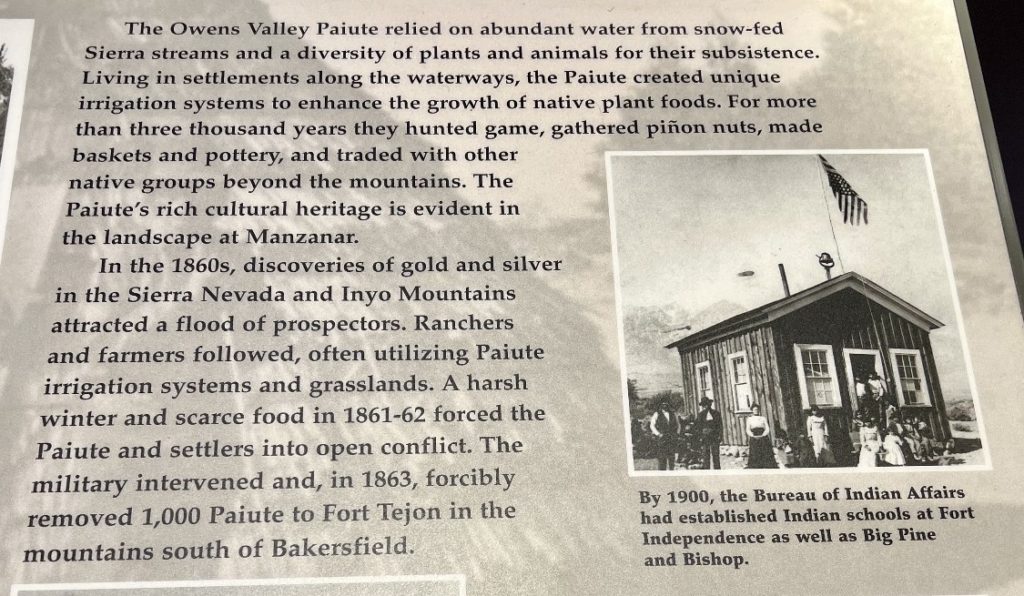

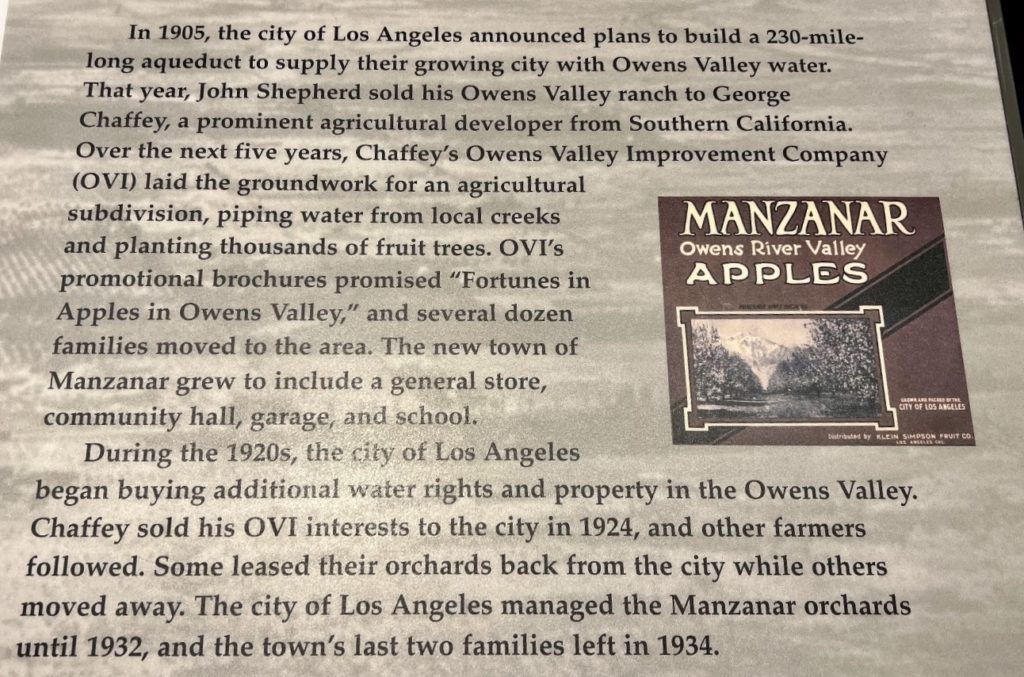

Beginning in the 1850s, Chinese workers on the Transcontinental Railroad and in California’s gold mines transformed the labor pool in the West. In the spring of 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed calling for a 10-year ban on Chinese laborers immigrating to the United States. Because of the Exclusion act, the need for unskilled workers led to a wave of Japanese immigration. Over the next four decades, several thousand Japanese immigrated to the U.S. Over time, many started businesses and families.

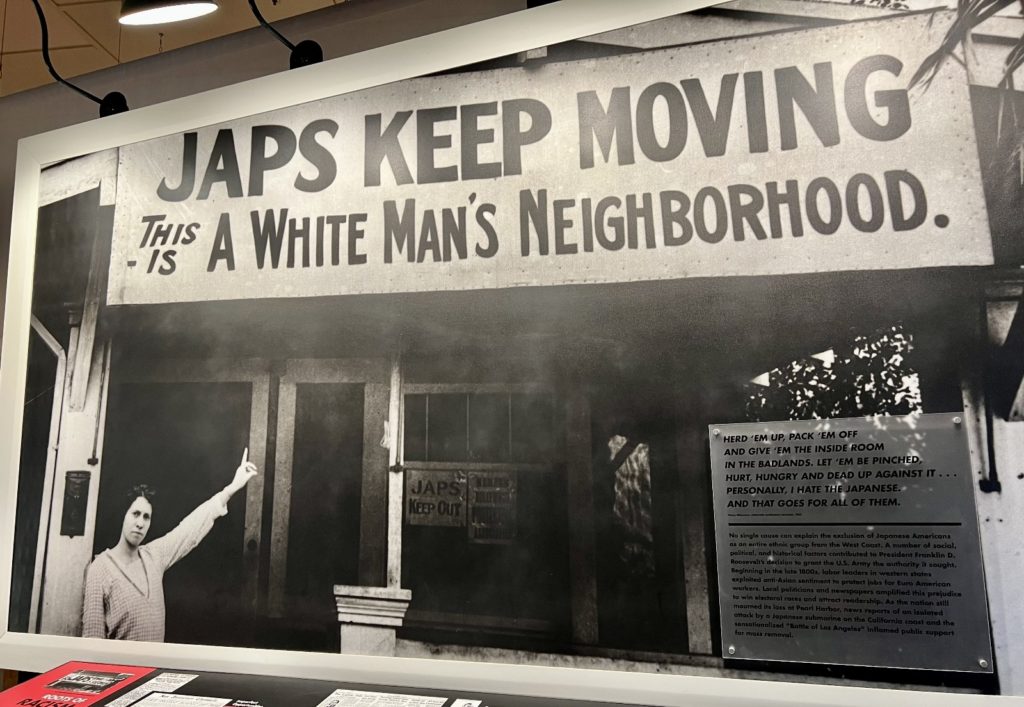

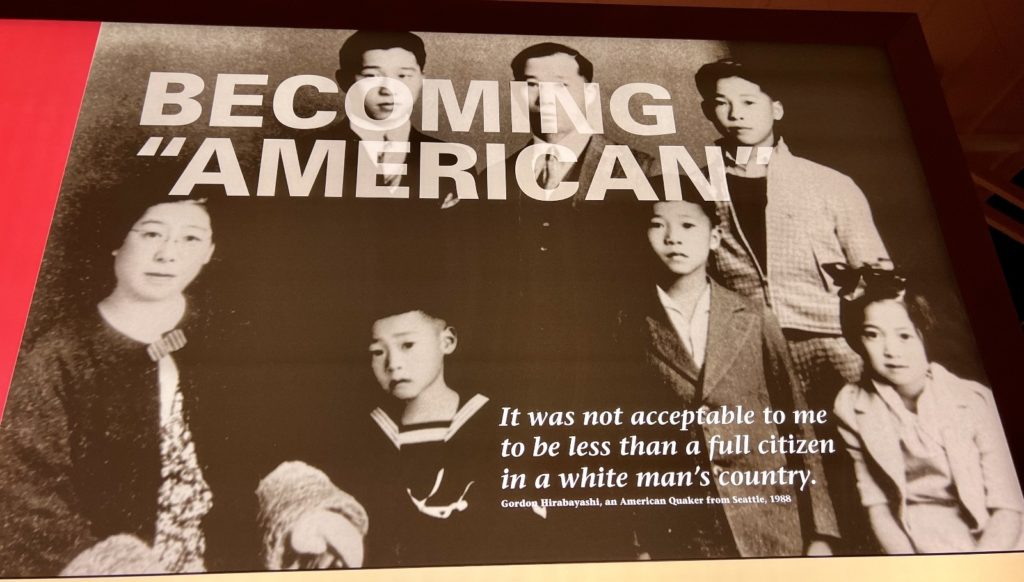

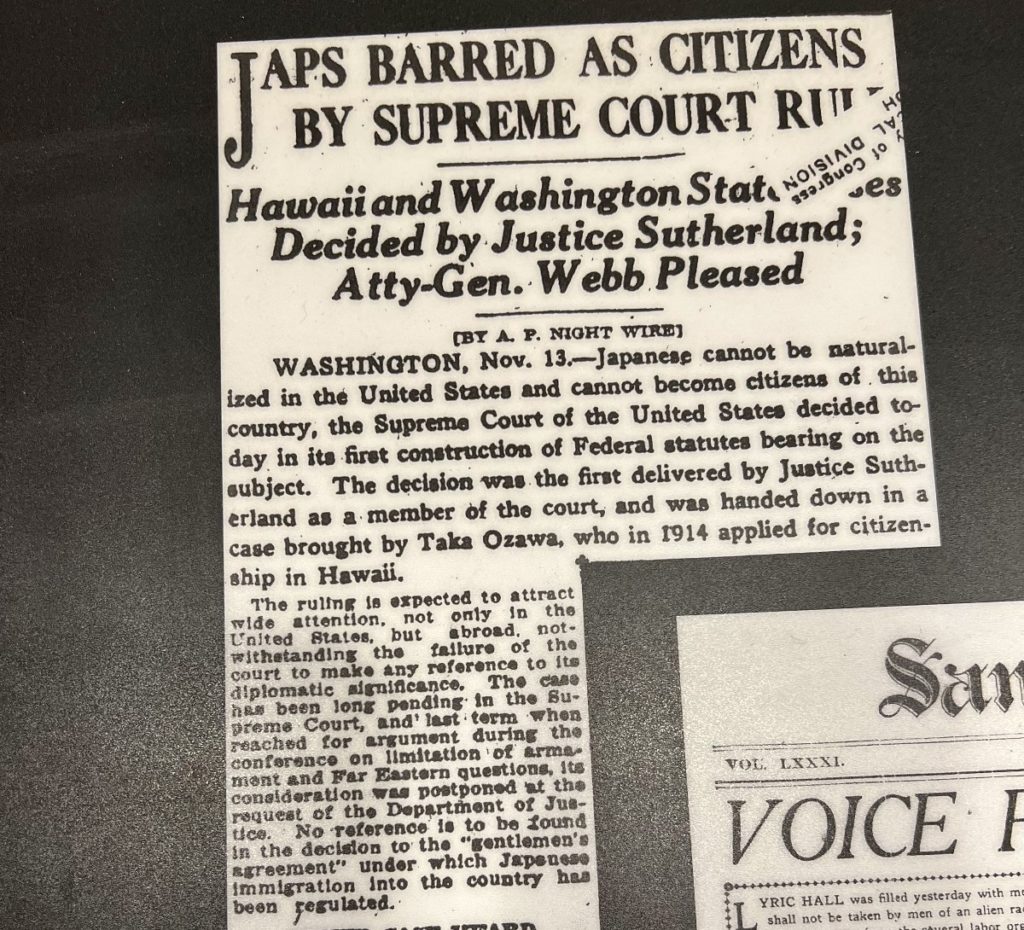

Many white Americans were suspicious of Japanese immigrants who looked different and were of a different culture. Over time, a series of laws were passed to limit their rights. In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law preventing Japanese from owning land. In 1924, the Immigration Exclusion Act effectively prohibited further immigration from Japan and barred Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military launched a surprise attack on the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack killed an estimated 2,400 U.S. personnel and destroyed or damaged 19 U.S. Navy ships. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared war on Japan the next day, and on Germany and Italy three days later. On February 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the U.S. military to carry out the exclusion and detention of American citizens and resident aliens. Although the order did not specify any ethnic group by name, in practice it applied to German and Italian aliens as individuals, but to all people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast.

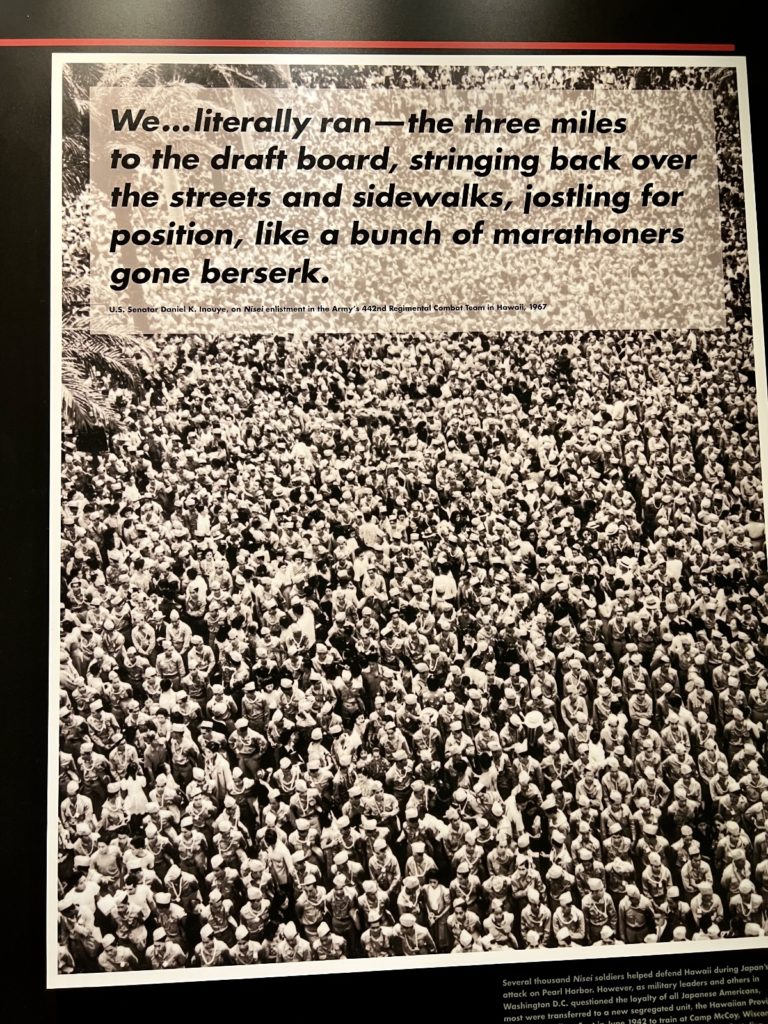

Several thousand Nisei (second generation Japanese American) soldiers helped defend Hawaii during Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. However, as military leaders questioned the loyalty of all Japanese Americans, most were transferred to a new segregated unit. In 1943 when the Army announced the formation of the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Turnout in Hawaii far exceeded expectations.

Not all politicians and military leaders doubted the loyalty of Japanese Americans. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover found “no factual data” which justified the mass relocation. Attorney General Francis Biddle believed the action clearly violated the U.S. Constitution.

We should never have moved the Japanese from their homes and their world. It was un-American, unconstitutional, and un-Christian.

-Francis R. Biddle, U.S. Attorney General, 1944

Welcome to Manzanar War Relocation Center

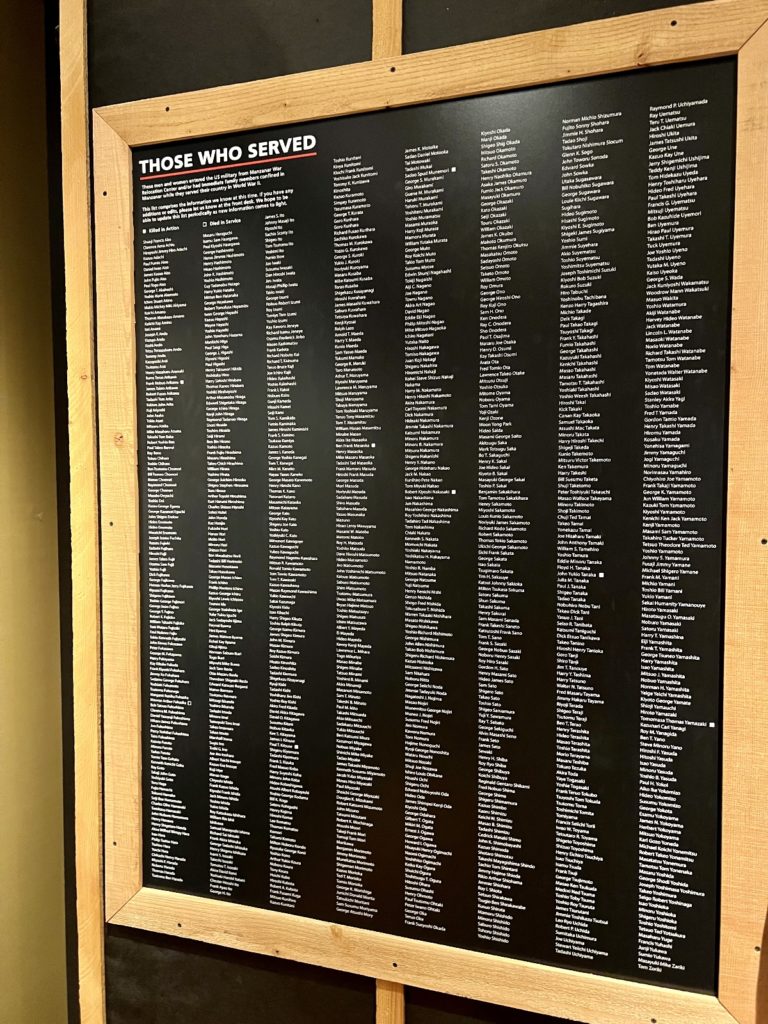

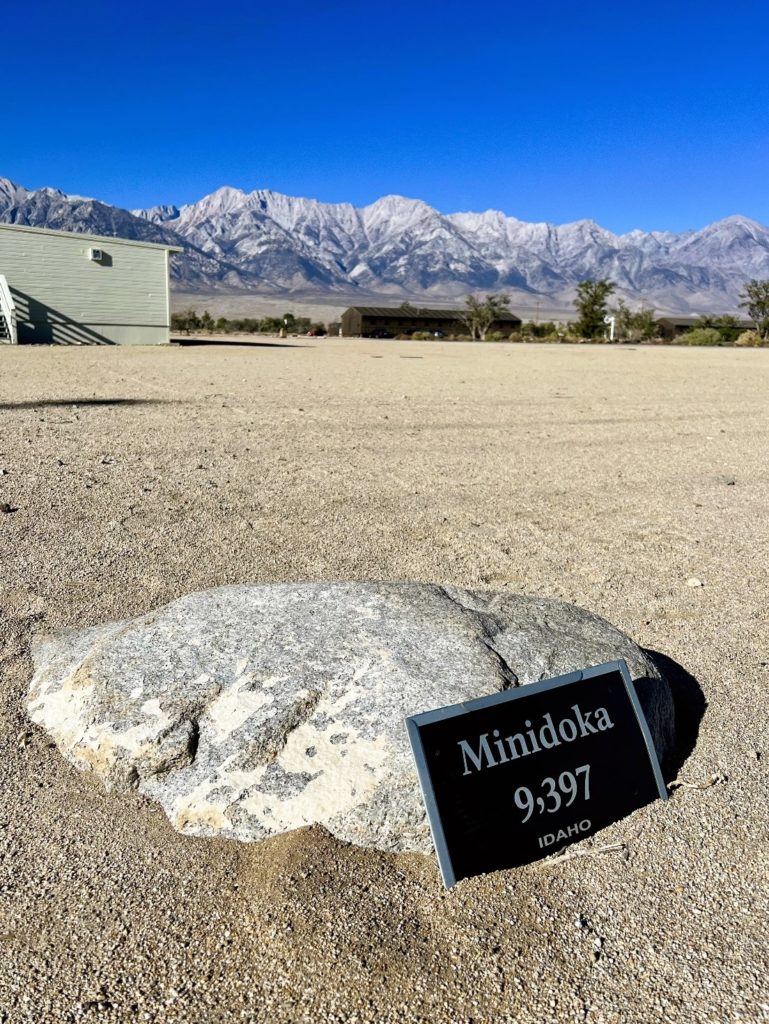

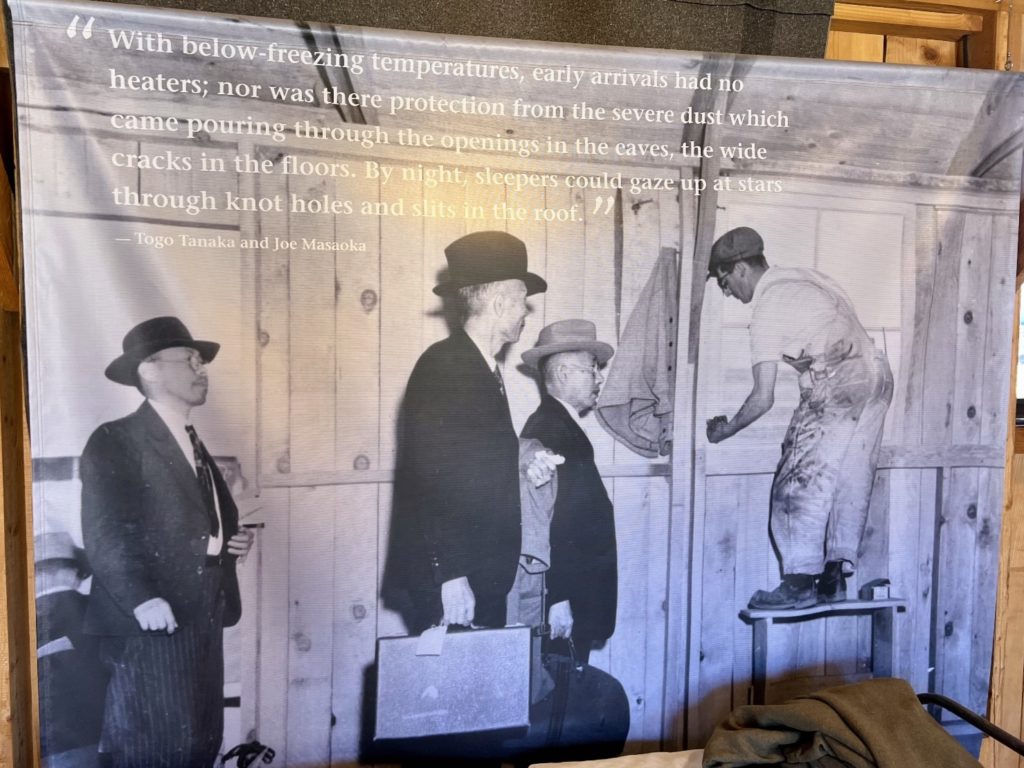

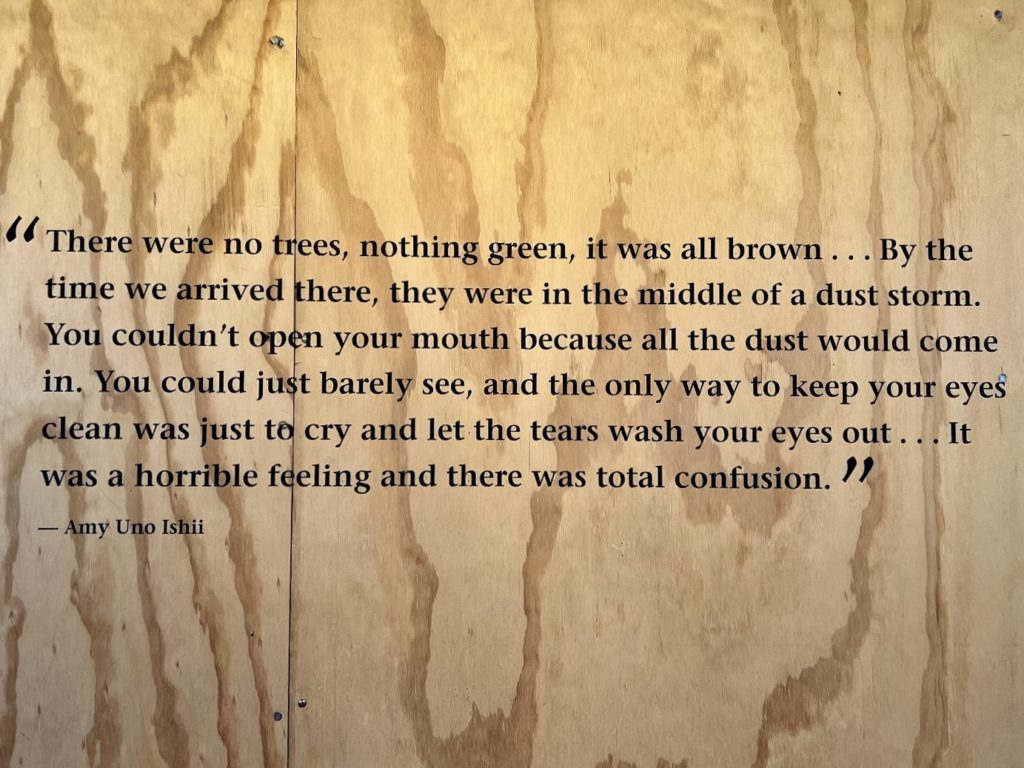

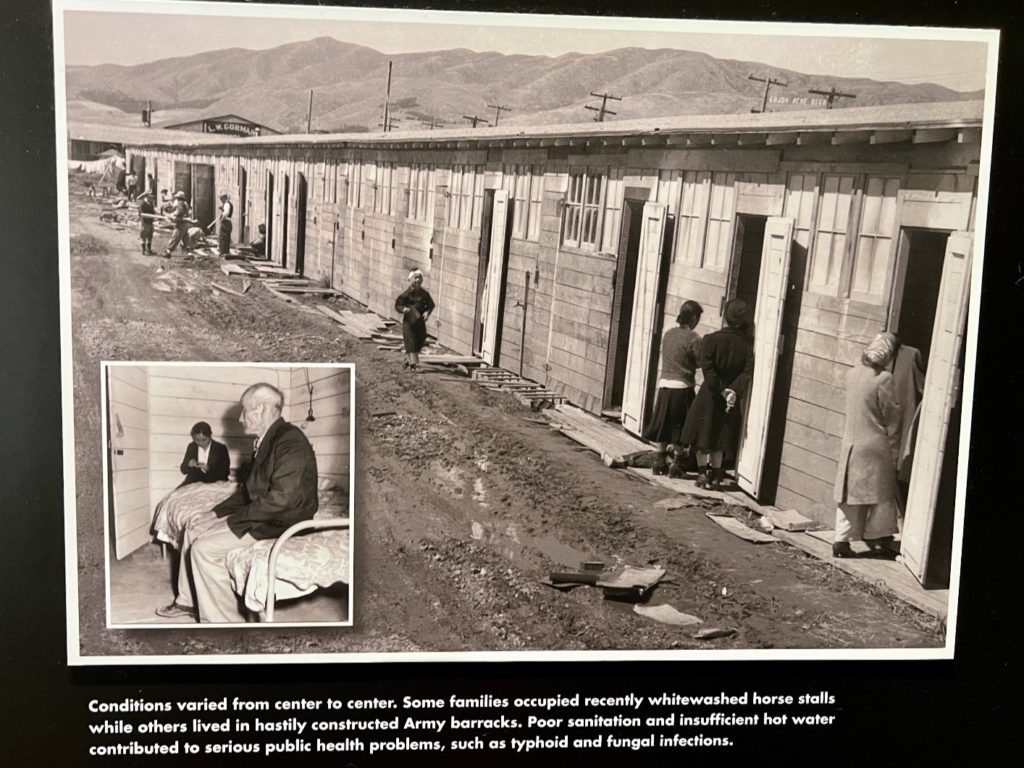

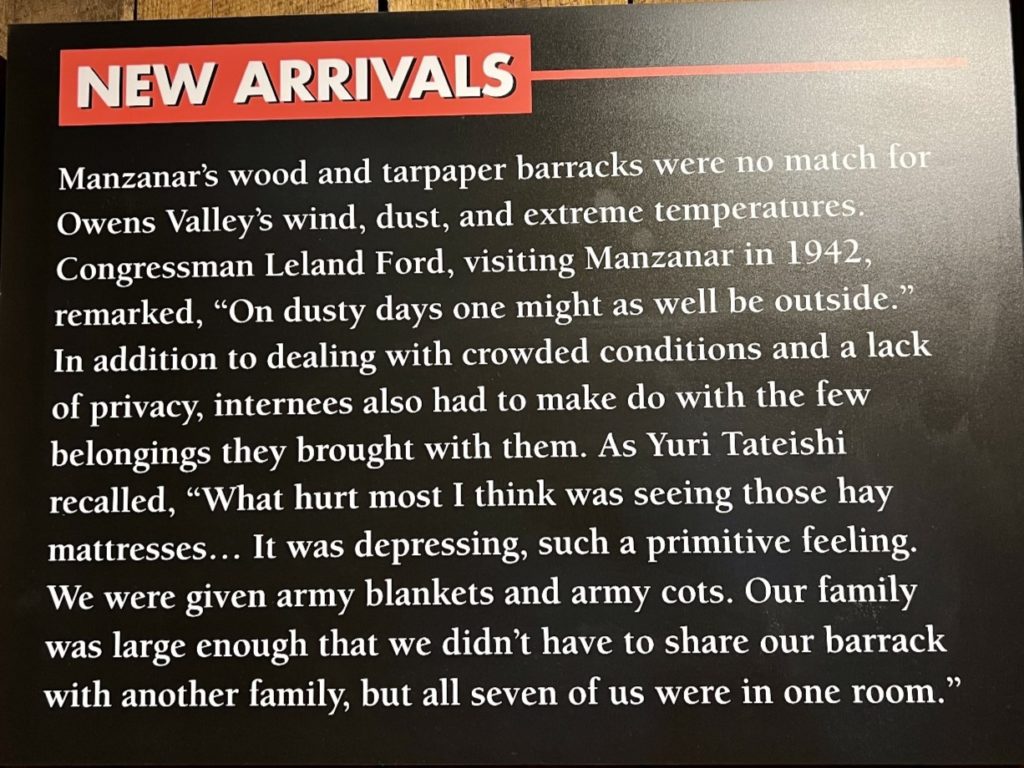

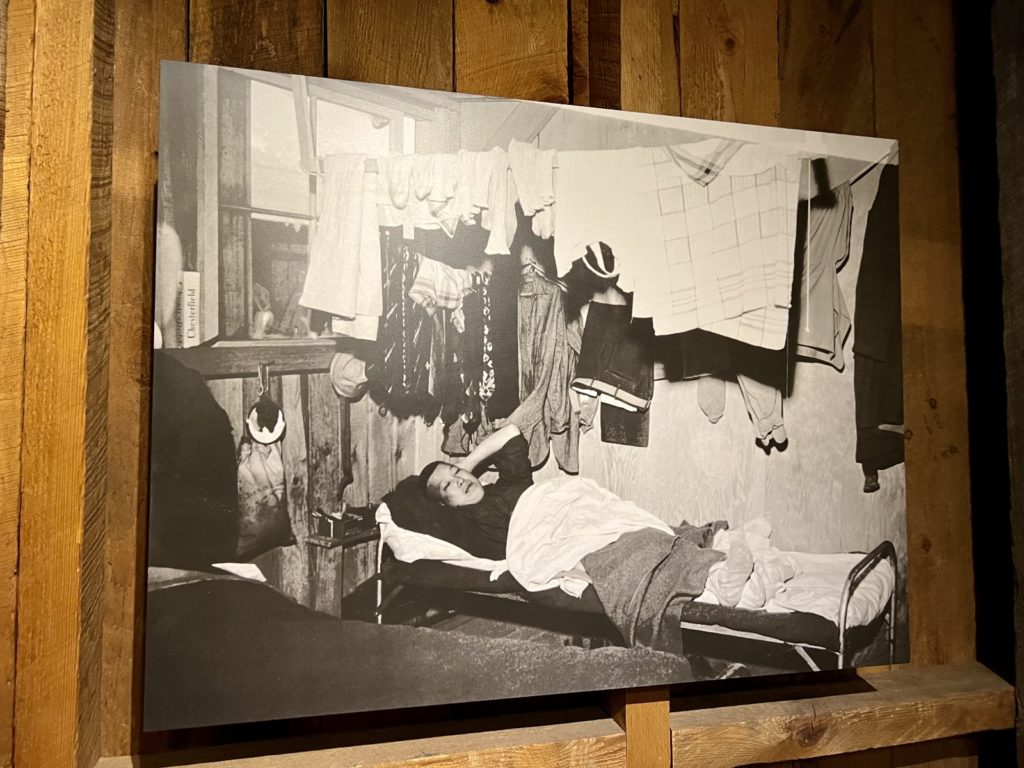

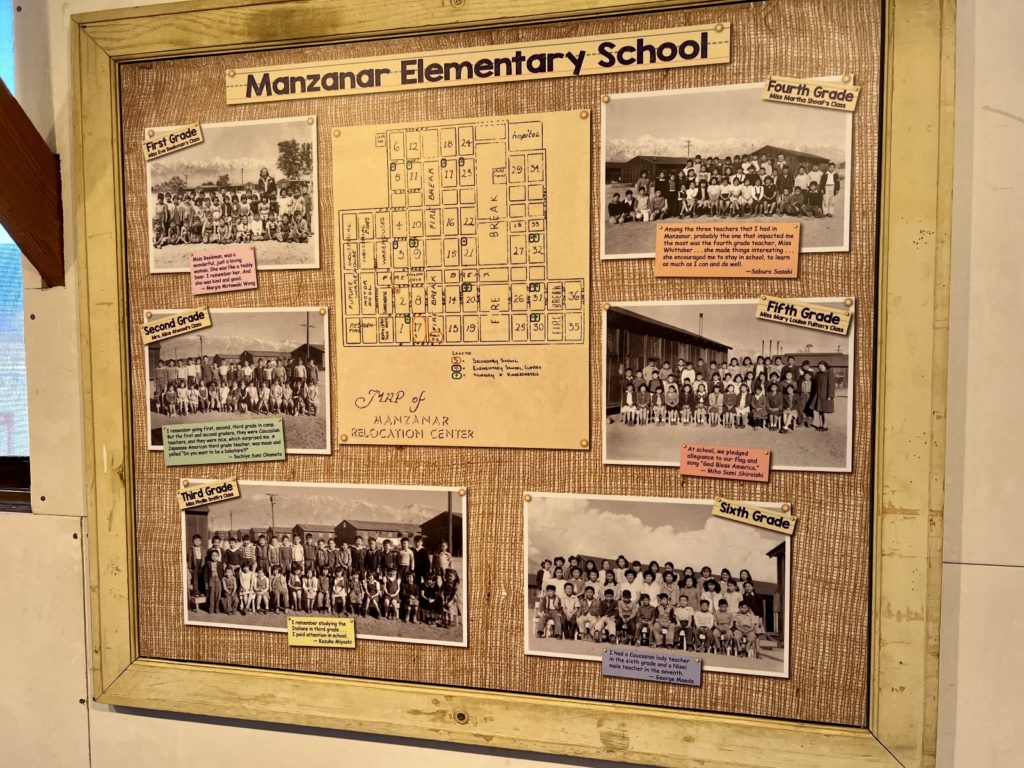

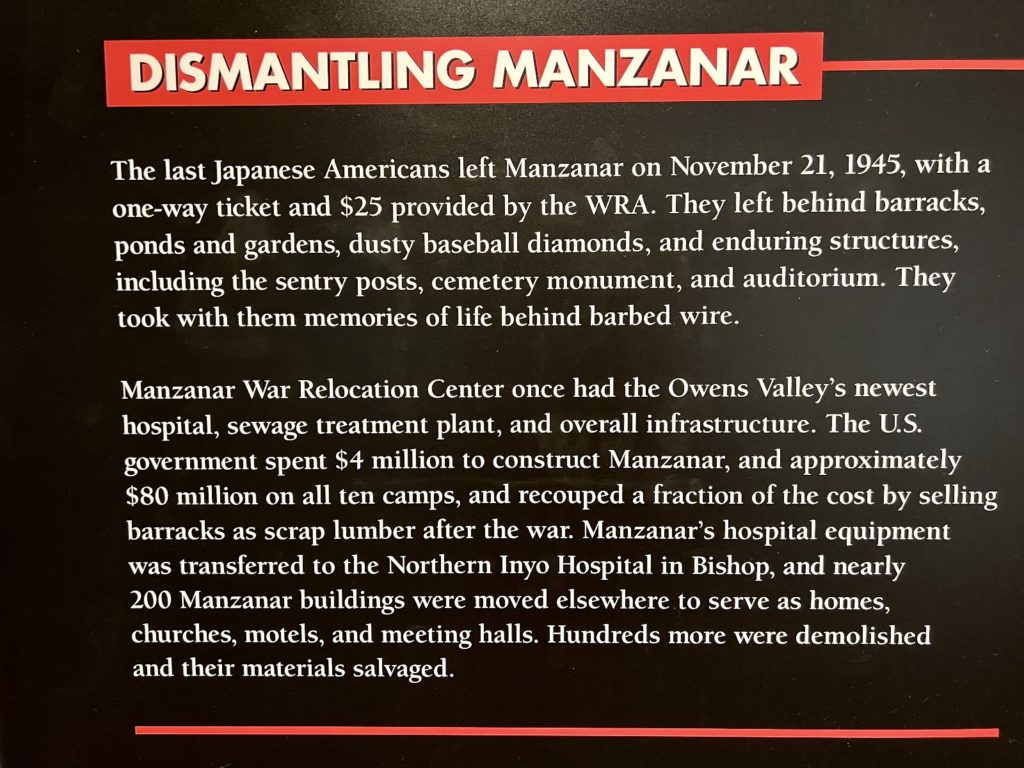

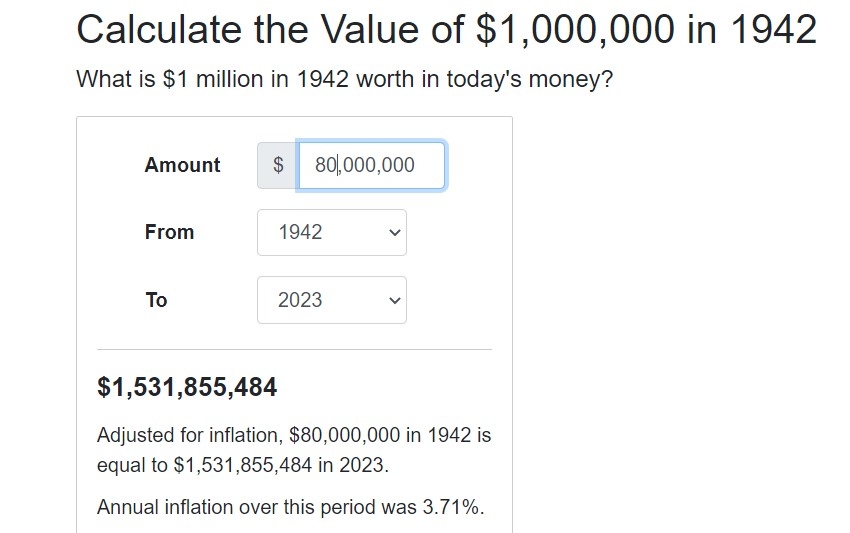

Our visit to Manzanar began at the visitor center located in the old auditorium building, one of just three original buildings remaining. We spent a significant amount of time looking at the museum exhibits which focused on the history of the Manzanar town site as well as life before, during, and after World War II for those of Japanese ancestry. Exhibits included historic photographs, artifacts, a scale model of Manzanar War Relocation Center, and a massive graphic that included the names of every Japanese American who spent all or part of World War II at Manzanar.

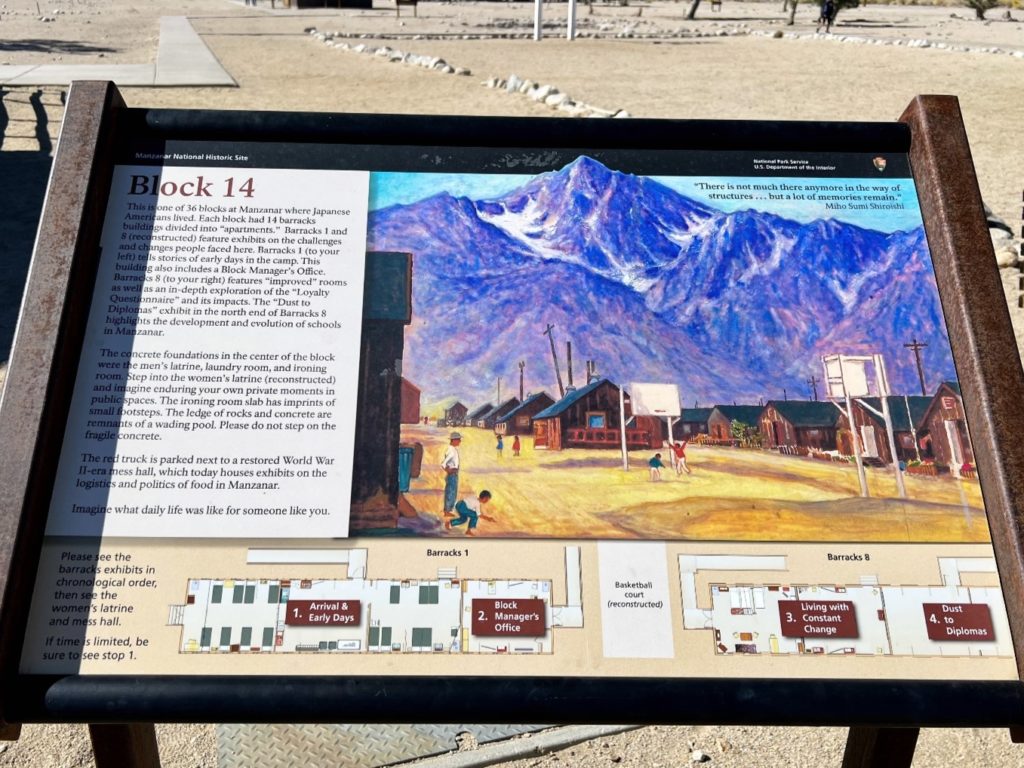

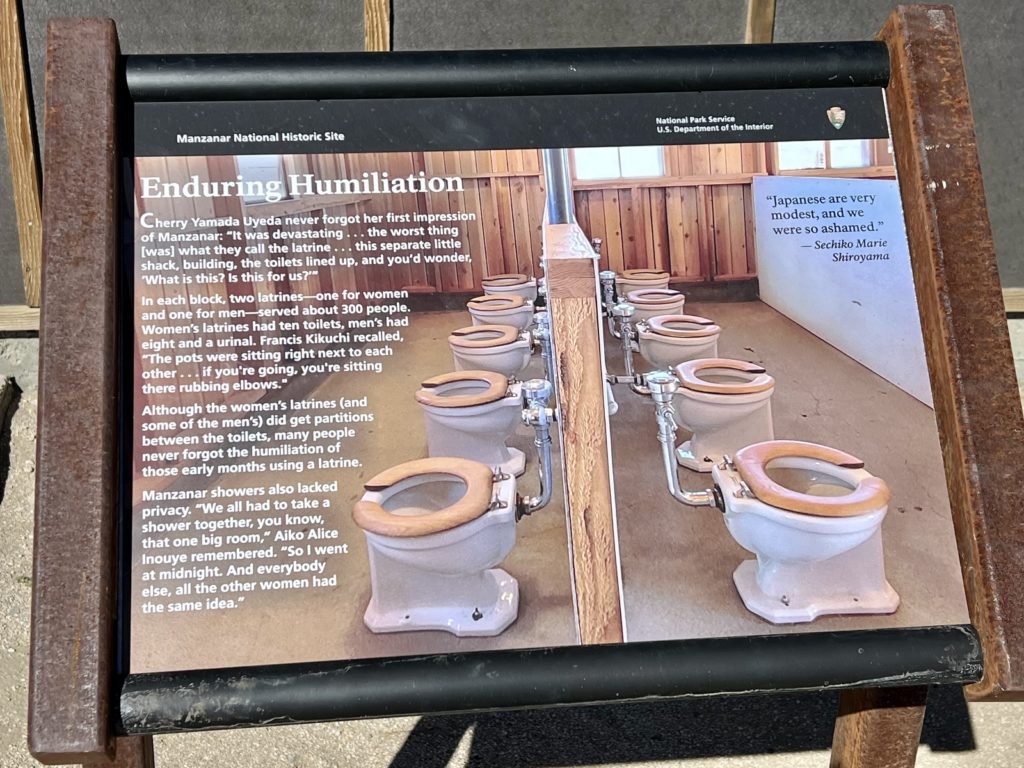

Moving on from the visitor center, we began the 3.2 mile self-guided driving tour with a stop at the demonstration buildings of Block 14. There we walked through two reconstructed barracks, a women’s latrine, and a remodeled WWII era mess hall. This complex of buildings helped us learn about daily life at Manzanar.

Our next stop on the driving tour was at Merritt Park. The people incarcerated at Manzanar left a lasting legacy by creating more than 100 Japanese gardens. The rock gardens and pools served as a source of peace and an escape from the harsh realities of incarceration and daily life. After Manzanar closed in 1945, many of the gardens disappeared as debris from demolished barracks, sand, and vegetation covered them. Recent archeological excavations have uncovered and stabilized some of these gardens including Merritt Park, the most impressive of the parks.

Our next stop was to view the iconic cemetery monument. In 1943, the people at Manzanar decided to erect a monument to honor their dead. The cemetery serves as a poignant reminder that 150 of the Japanese Americans incarcerated at Manzanar never saw freedom again. Many were cremated, in the Buddhist tradition, and some were sent to their home towns for burial. Fifteen people were buried in a small plot of land just outside the camp’s security fence. When Manzanar War Relocation Center closed, the families of nine of the deceased removed the remains of their loved ones for reburial elsewhere. Six remain at the site including Baby Jerry Ogata.

Wrapping up the driving tour, we made brief stops at the remains of the hospital as well as the sentry posts and guard towers. We spent about three hours at Manzanar. We could have easily spent many more hours there reading exhibits and walking around more of the gardens. I’d recommend allowing about half a day to visit Manzanar. But even if you only have an hour to spare, a stop at the Manzanar Visitor Center would be well worth your time.

Manzanar National Historic Site is located on the west side of U.S. Highway 395, 9 miles north of Lone Pine, California and 6 miles south of Independence, CA. There is no fee to visit. The Manzanar Visitor Center offers extensive exhibits, a 22-minute park film, a bookstore, a Junior Ranger program, and an information desk. It is open daily from 9:00 AM to 4:30 PM (closed on Christmas Day). The driving tour and grounds are open daily from sunrise to sunset.

The Adventure Continues

This wraps up the posts from our time in and around California’s Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains. Join us for our next post as we move to Southern Nevada and make an unexpected visit to nearby Zion National Park for our longest hike yet. And don’t forget to check out our Amazon RV and Adventure Gear recommendations. We only post products that we use and that meet the Evans Outdoor Adventures seal of approval. By accessing Amazon through our links and making any purchase (even things as simple as toothpaste!), you get Amazon’s every day low pricing and they share a little with us. This helps us maintain this website and is much appreciated!

A beautifully written and thought provoking blog post! I’ve been by Heart Mountain in Wyoming several times, but never have been able to visit, but I know I really need to make that effort. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you Heidi, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. It sure was a tough one to write and I hope I did it some justice. Heart Mountain is on my list of places to see. I hear it is very well done. We were supposed to go Sept 2022, but our kitty got quite sick and it delayed our travels causing us to miss out on the Cody, WY. The National Park Service is developing another site in Colorado (Amache). I hope to visit it some day.

By the way, I really like the National Park Unit map you have on your website and the color coding for units that you’ve visited. That looks like a ton of work, but super cool! I really need to do something like that. Hoping to see all of them eventually!

Happy trails,

Lusha

BRAVO, my friend!! You told the difficult story that cannot be left untold.

Thank you friend. Such a life changing experience. A place every American should experience.